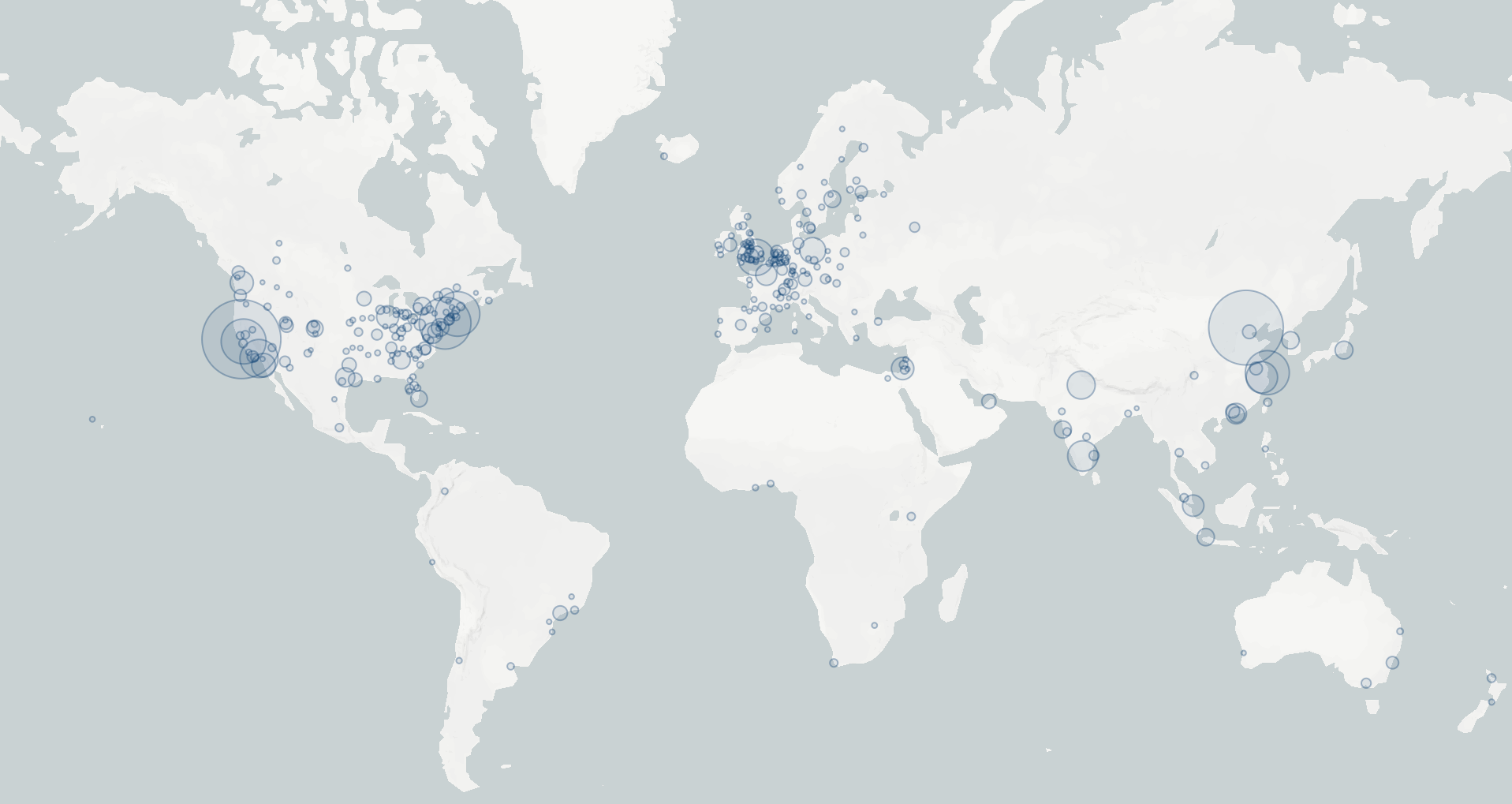

To document the world’s leading startup hubs, we used data from PitchBook Data, Inc., which captures the geographic location of companies that received venture capital investment. We grouped the metro-level data into three three-year periods—2005-2007, 2010-2012, and 2015-2017—to reduce noisiness from year to year, especially in smaller geographies. These figures were broken down by country, state or province, city, and postal code for each company’s headquarters. The data was then cleaned for any spellings or identification errors.

Once the raw data was cleaned and tabulated, we grouped these data into broader metropolitan areas based on their country-state-city-postal code combination. While most of these places are metropolitan areas, a few are non-metropolitan areas. Startup activity in the U.S. was mapped to metropolitan or micropolitan areas using Census Bureau data. Startup activity in the European Union was mapped onto metropolitan, intermediate, or rural areas (at the level of NUTS 3) using Eurostat data. The rest of the world’s aggregations were made only by metropolitan area, using a combination of files from national statistical authorities (e.g., Canada, Israel) or international sources (e.g., Brookings Institution, World Bank, Oxford Economics, ESRI, Google Maps). This produced a list of relevant geographic areas for each deal in the PitchBook database (or confirmed blanks where no corresponding area existed). Deals that occurred in another area of a country were grouped into an “other” category.

Next, these data were fed back to PitchBook for the aggregation of deal counts according to our specified geographic areas for each of the three-year periods and across one of four round types: angel and seed-stage, early-stage venture, later-stage venture, and mega deals of more than $500 million. The nearly 100,000 venture deals in the PitchBook database, which cover nine years of collected data that span a period of 17 years, collectively produced more than 5,000 combinations (cells) of deal activity along our aggregations of geography, time period, and round type.

In addition to the number of deals, PitchBook extracted two other measures: the amount of capital invested in these deals (where the amount invested was reported) and the number of deals in which the amount of invested capital was reported. As a result, the amount of capital invested for 17 percent of the nearly 100,000 deals was not reported. Since our aim is to analyze both deals and capital invested (dollars), we conservatively interpolated values for these approximately 17,000 deals. To do this, we first tabulated global average deal sizes for each of the 12 round-period combinations. We then assigned geographic areas into quartiles for global deal volume in each period and round type. Each of the four groups in each period was assigned an adjustment factor of 40 percent, 50 percent, 60 percent, or 70 percent (from the lowest deal activity group to the highest).

For each geographic area with a deal reported, but a missing value for the capital investment, we assume that the deal size is the global average for that period-round, reduced by the relevant adjustment factor. In other words, the places with the fewest deals are assumed to have relatively smaller deal sizes compared to the global average, while the most active places are assumed to have relatively larger deal sizes. In all cases, missing deals are assumed to be smaller in general, as each adjustment factor value is far less than 100 percent (an adjustment factor of 100 percent would indicate an equivalent of the global average). These new adjusted figures have the effect of raising the level of capital invested by 10 percent globally over the three periods compared to capital invested when missing deal size values were not interpolated.

Next, we mapped each geographic area onto its population estimate for the most recent period, 2015-2017. To make this process manageable, we filtered out all but 500 of the most active regions for venture deals in the most recent period. From there, we applied population figures from a variety of sources. For the U.S., Canada, and Israel, figures came directly from national sources. Europe’s figures came primarily from the Eurostat, though there were a few exceptions for smaller areas in Ireland, Finland, Sweden, and the United Kingdom, which came directly from national sources. Aside from these, population data for the rest of the world came from Oxford Economics (via the Brookings Institution) or the United Nations.

With a nearly complete dataset in hand, we applied two final filters. The remaining geographic areas needed to satisfy two conditions: (1) a population of at least 100,000 residents in the most recent period (2015-2017), and (2) a minimum of six venture capital deals in the two most recent periods (2010-2012 and 2015-2017), or an average of two deals per year within each of the three-year periods.

This resulted in a final list of 314 geographic areas—primarily metropolitan areas, but also a small number of micropolitan (U.S.), intermediate (EU), and rural areas (EU). These 314 startup hubs cover 92 percent of total venture deals and 96 percent of total venture capital investment in 2015-2017. For each of these 314 hubs, we tabulated figures for venture deals, venture capital invested (adjusted), and a measure that caps deal sizes at $500 million to control for the effect of very large mega deals. Each of these three measures is available by round (pre, early, late, mega) and period.

Our typology of startup hubs is based on the level of venture capital deals, the volume of venture capital investment, and the change in both. We used our capped figures for venture capital investment (which limits all deals to $500 million in size) to reduce the influence of cities that have total activity driven to a very large extent by these massive outliers.

We next benchmarked each metropolitan area against the within-measure maximum (i.e. the leading city received a score of 1 for each category) and created a composite score across all measures for each city. The scores were then assessed to look for statistically meaningful breaks in the data and to discern natural groupings. These were also crosschecked with several iterations of statistical clustering analyses through the k-means method.

Based on this, we identified two main types and seven individual categories of Global Startup Hubs. The first type is comprised of large Established Global Startup Hubs, which span 64 individual metropolitan areas. For this exercise, we combined the San Francisco and San Jose metros into the San Francisco Bay Area and the Raleigh and Durham metros into the Research Triangle, to produce 62 Established Startup Hubs.

The second type is comprised of smaller Emerging Global Startup Hubs. The Global Next are cities within the top 100 for total venture deals and a strong presence (relative activity) and growth of angel and seed-stage investment. Each is among the top 60 for such deals. We simply selected the top 10 from the list, as we did for all Emerging Startup Hubs. For the Little Giants, we took the remaining metros with the highest per capita measures for venture deals and venture capital investment by calculating a composite relative metric across both. For the Global Gazelles, we calculated a composite metric for relative growth rates in venture capital deals and venture capital investment and took the remaining ten cities with the highest scores.